Kyasanur Forest Disease - causal agent and transmission cycle

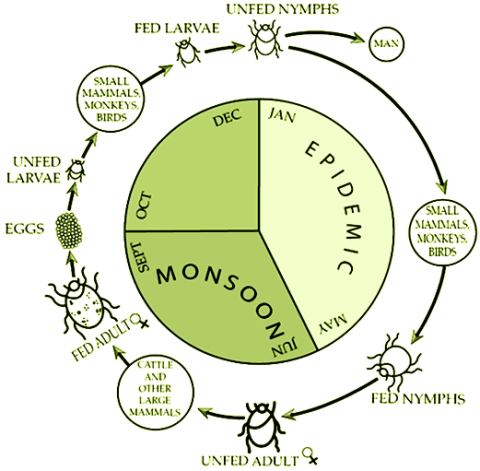

KFD, also referred to as Monkey Fever, is a tick-borne viral haemorrhagic disease, which can be fatal to humans and other primates. The causal agent, Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus), is a member of the tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) complex. It is transmitted by a range of tick species, with Haemophysalis spinigera being considered the principal vector. A wide range of small rodents, monkeys and birds are thought to play a role in Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus (KFDV) transmission. Cattle are probably important hosts for adult H. spinigera ticks but develop neutralising antibodies against KFDV which suppress virus amplification.

Humans, who contract KFD virus when bitten by an infected tick or by coming in contact with an infected animal, are considered dead-end hosts. This is because they cannot infect ticks nor other people with the virus and hence do not play a role in the onward transmission of KFDV.

Who is affected?

KFD first emerged in Kyasanur Forest in the Indian state of Karnataka in the 1957, after this forest ecosystem became increasingly degraded by human activities. Since 2012, Kyasanur Forest Disease has spread to new districts and states within India, and human cases have increased significantly to around 500 each year. Between 5 and 10% of people who are known to be affected by KFD develop haemorrhagic symptoms and die. There have been at least 340 confirmed deaths from the disease over the last five years.

People most affected by Kyasanur Forest Disease live in low-income forest communities and include:

- resident and migratory farmers who graze animals (largely cattle) in the forest year-round to produce manure for plantations

- tribal forest-dwellers who harvest fuel wood and non-timber forest products, such as honey, nuts, and dry leaves

- day labourers in plantations or for State Forest departments

Livelihoods are impaired by when people avoid the forest due to the risk of Kyasanur Forest Disease or due to death and sickness of family members that principally generate household income. Although KFD is managed through vaccination, information campaigns and tick protection measures, lack of awareness about the disease and poor vaccine uptake can prolong and exacerbate epidemics.

Why is KFD risk higher in degraded and fragmented forest?

The risk of contracting Kyasanur Forest Disease is thought to be higher in fragmented and degraded forests because KFD first appeared when forests were cleared for mining, road building and agriculture in the 1950s.

However, we lack data on the ecology and socio-ecology of the Kyasanur Forest Disease system to test this hypothesis and to identify high risk areas for the disease.

Many tick, wild rodent, bird and primate species are thought to have a potential role in transmission of the KFD virus. But crucially, it is not known how these potential host and vector species are linked to forest types, and which ones are key in transmitting KFD to people as forests become more degraded or open due to human activities.

Similarly, work is urgently needed to understand how the specific activities of local communities in the forest increase their risk of contracting the disease, and whether and how such activities could be avoided without harming their health and livelihoods.